Preparing for emergencies

By Susan McNaughton

Public Information Officer, PA DOC

Reprinted with permission from the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections

In February 2003, President George W. Bush issued a Homeland Security presidential directive calling for the development and administration of a National Incident Management System (NIMS) to provide a consistent nationwide template that all government agencies, private- sector companies and emergency responders can use to work together during domestic incidents, disasters, catastrophes, etc.

NIMS establishes a consistent operational structure and language so everyone is working on the same page and speaking the same language during emergencies. One of the most important “best practices” that has been incorporated into NIMS is the Incident Command System (ICS), a standard, onscene, all-hazards incident management system already in use by firefighters, hazardous materials teams, rescuers and emergency medical teams. The ICS has been established by NIMS as the standard incident organizational management structure.

The ICS drill begins with the arrival of the drill’s coordinator. The visiting room officer is arranging for SCI Coal Township Critical Incident Manager Lt. Russell Feese (center of picture) to go inside the prison to facilitate an incident in one of the prison’s exercise yards. |

Because Governor Edward G. Rendell has directed the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections to always have excellent emergency planning strategies, switching over to ICS wasn’t too difficult to implement. The change began with experienced corrections professionals, some being retired superintendents and even a former corrections commissioner, providing training to DOC high-level managers. Training was then provided to other middle managers and to all facility staff.

Today, the DOC continues its ICS training in the field by holding surprise, unannounced ICS drills. These drills begin with Captain John Eichenberg (the DOC’s critical incident manager coordinator/assistant chief of security and head emergency preparedness liaison officer) and several others involved in carrying out the drill, arriving at a state prison and declaring they are there for a surprise drill. Eichenberg and the others split, with Eichenberg going to the superintendent’s office and the others going into the facility to begin the emergency situation. Situations range from hostage incidents to severe structural damage caused by tornados.

As the ICS drill begins at SCI Cresson, key players begin to take on their roles as section chiefs and recorders. This scenario involved a hostage situation outside the prison perimeter. |

The ICS drill actually begins when a call is received at the prison’s control center indicating the drill has begun. From there, the facility manager (which is the highest-ranking official on site at the time of the drill) determines whether to handle the situation at the control center or whether to activate the ICS command post.

An emergency inmate count is held. So as to not be disruptive to the normal operations of the prison, after count clears, inmates are permitted out of their cells to continue with normal prison life. Behind the scenes, though, a drill is ongoing.

If the command post is activated, the facility manager – who is now referred to as incident commander under the ICS system – designates individuals who will serve as chiefs of key responsibility areas, such as operations, logistics, planning and finance. Each chief has a checklist of things to accomplish during an incident that is based upon their area of responsibility or expertise.

The incident commander can select whomever he/she wants to serve as chief of an area. For example, under the old way of handling an incident, it may have been appropriate to have a deputy superintendent serve as the chief of planning. However, under ICS, the incident commander relies on an individual’s expertise and ability, rather than a title. Under ICS, it is more appropriate to make a fire safety manager the planning chief if the incident involves a fire. The ICS system’s flexibility allows the manager to use appropriate people, regardless of their title, to resolve an incident quickly and successfully.

A number of other individuals also serve as recorders for each section’s chief. In addition, the public information officer and a recorder specifically for the incident commander all are in the command post monitoring the situation at hand.

The section chiefs work with their appointed employees within their section to help the incident commander oversee the incident. The sections break off into working groups, and the section chiefs frequently gather or regroup with the incident commander to provide the incident commander with regular updates, plans of action, etc.

This designation of personnel and the sections is standard under ICS. Every agency, organization and company utilizes the same structure. The ultimate goal during the drill, as with a real incident, is the handling of the incident so there is a successful resolution. Officials gather information to determine exactly what has happened, what needs to be done to resolve the matter, what needs to be done to recover from the incident, and finally, to collect all notes and information to provide a final report on the incident.

The DOC uses a number of wall charts during an incident to organize information, and to make that information available at a moment’s notice to new people entering a command center. |

As we all learned from the 1989 SCI Camp Hill prison riot, some incidents don’t take place neatly between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. on a weekday. They can happen at any time – day or night – and can even start again after everyone presumes the situation is over.

Because of this, the DOC holds these surprise ICS drills at any time – day or night, weekday or weekend.

“We want the training to be as realistic as possible,” said Capt. John Eichenberg. “That’s why we hold them at a moment’s notice. We want to help individuals who may not necessarily be in charge during a normal work day to be able to handle a situation, because if they are the highestranking official at any given moment, they could, under ICS, be an incident commander.”

Eichenberg said it’s better for employees to have an opportunity to use the ICS system during a drill so they can get used to the structure and language. “We prefer that employees learn the system and become comfortable with it before an actual incident occurs.” And the drills are not necessarily reserved for just DOC employees. Individuals from the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency, the Pennsylvania State Police, local and township emergency responders and others necessary to resolve a scenario are included in and participate in the surprise drills.

“While we work within the DOC to ensure we’re using the appropriate structure and language, it is also important to work with outside entities to ensure those lines of communication and familiarity with the various individuals become comfortable,” Eichenberg said.

While not every DOC state prison has had the privilege of having a surprise ICS drill, each one is slated to do so before the end of 2007, and continued,ongoing training and drills will take place well into the future. Employees are encouraged to review the ICS policies, checklists and forms, and they should participate in training that is provided at the DOC’s Training Academy, at their facilities and via computer.

The beginning of an ICS drill at SCI Mahanoy. The scenario was a sink hole and collapsed handball court wall with injuries to inmates and staff. At the onset of the drill, the incident commander, Deputy Superintendent Thomas Temperine (far right), monitored the situation from Control. |

“When it comes to emergencies, you can never be too prepared,” said Eichenberg. “That’s what makes these drills so vital. Our number one priority is providing for public safety, and using the ICS system ensures we do that in a manner that is on the same level as everyone who possibly may assist us during an actual emergency situation.”

As the ICS drill begins at SCI Cresson, key players begin to take on their roles as section chiefs and recorders. This scenario involved a hostage situation outside the prison perimeter. Hostage negotiators at SCI Cresson make contact over the phone with the hostage taker during the ICS drill. In Control, SCI Mahanoy had a special ICS binder for each individual type of scenario. Depending upon the incident, they pull out the appropriate binder and begin completing the appropriate ICS forms.

Continuing with surprise ICS drills: Is your turn coming? YES!

Tuesday, June 26th was a lucky day — or unlucky day depending upon how one views an unannounced visit by Central Office Capt. John Eichenberg and his entourage – for officials at the State Correctional Institution (SCI) at Chester. Eichenberg, who is responsible for coordinating and holding unannounced Incident Command System drills at each state prison, arrived at the prison at 9:30 a.m. and with his two facilitators got to work. One went to the scene of the drill scenario and the other went to Control. Eichenberg made his way to the superintendent’s office, where he instructed the secretary to interrupt the weekly staff meeting.

Technically, the drill had not yet begun, but this is the way it all starts. The drill began when SCI Graterford Critical Incident Manager (CIM) Scott Bowman commandeered a state flat truck and entered the prison’s sally port as a passenger. Once Control was notified of the situation, they immediately began their ICS procedures, where they were observed by Walter Grunder, another SCI Graterford CIM.

Finally, Supt. Thomas was notified of the situation, but was not yet the incident commander. His actions, and those who would man the command post, were observed by Eichenberg. The scenario for this drill was an outsider carrying a bomb onto prison property and threatening to detonate it if his friend, an inmate, was not released from prison. Because a staff member is in the truck and another is in the sally port and was instructed by the outsider not to move – this situation had become a hostage situation.

ICS has several features that make it well suited to managing incidents:

|

Due to the command post’s close proximity to the sally port, the decision was made to move the command post to its alternate site. Later, in the middle of the drill, the fire alarms went off – it’s another twist that Eichenberg ikes to put in his drills. So now the command post has to relocate to a second alternate site. Thankfully, the relocation was simulated.

SCI Chester Superintendent John Thomas takes over as incident commander. Here, he meets with his section chiefs and directs recorders about what they should be writing on the laminated wall forms. The “bomber/hostage taker” and the employee are sitting in this truck inside the prison’s sally port.

As the drill progressed, immediate responders were dispatched to cordon off the area and the Corrections Emergency Response and Hostage Negotiation teams were both activated.

The drill was concluded around 1:30 p.m., and a “hot wash” followed. A hot wash is actually a debriefing that involves all individuals who participated in the drill – from recorders to CERT members to section chiefs and the incident commander.

“We hold these drills so you to practice,” Eichenberg said to the group. “We are not here to critique you or to issue a report card. We are here to allow you an opportunity to try out the ICS system and to work out any bugs you uncover during the drill. We want this to be a positive experience.” During the hot wash, most people commented that they would like to have more surprise drills held involving a variety of scenarios and at various times of the day.

In all, the drills allow people to see whether certain areas need further addressing, such as whether alternate sites are adequately equipped, whether there are issues with communication and to really think about the unique settings their prisons may face during an emergency situation – for example, Chester has a major roadway on two sides, a railroad track on another, a casino/raceway close behind it and is under the approach path to the Philadelphia International Airport.

“We want officials to be able to ‘play’ during a time when it isn’t an emergency situation, so they can be better prepared should one actually take place,” Eichenberg said. “Supt. Thomas and SCI Chester staff – just as the other prisons that have participated in surprise drills so far this year – should be pleased with their performances and look at the drills as learning opportunities.”

Because they were told to initiate contact with the “bomber/hostage-taker” using a cell phone without speakerphone function, the primary and secondary negotiators worked closely to gather information. |

This is the prison’s sally port. This is the casino. Everyone always wonders just how close the casino is to SCI Chester. This photo should help put it into perspective. During the “hot wash” following the drill’s conclusion, participants are given an opportunity to discuss the positive aspects of the drill and to discuss their concerns.

Because they were told to initiate contact with the “bomber/hostage-taker” using a cell phone and there was no speaker function on the cell phone, the primary and secondary hostage negotiators worked closely to gather information.

Educating others we may work with under ICS

In April, Captain John Eichenberg, who also serves as the DOC’s critical incident coordinator and assistant chief of security and head emergency preparedness liaison officer, addressed members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from Washington, DC, and generals, colonels and majors from the Pennsylvania National Guard at a conference in Gettysburg.

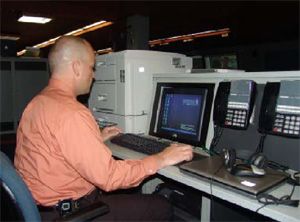

Captain John Eichenberg works at his EPLO station at PEMA’s Emergency Operations Center. |

During the presentation, Eichenberg provided attendees with information about the locations of the state’s prisons and a brief history of the DOC, as well as information about equipment or resources that could be made available to the National Guard in the event of an emergency. Eichenberg explained that the DOC centrally tracks all of its equipment, such as generators, heavy equipment and supplies, so they can be located and deployed on a moment’s notice.

This presentation was an effort of the DOC to show its willingness to assist other Pennsylvania agencies during an emergency or disaster and how the DOC uses the ICS system. General James R. Joseph, secretary of the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency, commented to Eichenberg that the presentation was excellent and very useful by allowing everyone an opportunity to see what resources the DOC has to offer during a major emergency.

PEMA’s Emergency Operations Center Responsible for Coordinating Resources

When an incident takes place in Pennsylvania, no matter where it is or the size of the incident, officials at the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) of thePennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) are on hand to monitor the incident and to provide assistance.

In addition to PEMA employees who monitor the state 24/7, various agency emergency preparedness liaison officers (EPLOs) are called in to help. For example, if there was a situation involving a landslide on a major roadway, PEMA would call in EPLOs from PennDOT, the State Police and, possibly, the Department of Environmental Protection and others, depending upon the nature and scope of the incident.

And, while people may not think the DOC would be of use during such an incident, that is not necessarily the case. The DOC maintains many pieces of large equipment that could be useful in clearing a roadway. So, the DOC’s EPLO could be called in as well. The DOC’s lead EPLO is Capt. John Eichenberg. Several years ago there were only two other individuals who served as back-up EPLOs. However, now there are eight others who volunteer to serve the Commonwealth’s citizens as DOC EPLOs.

They don’t receive extra compensation for this work, which has them on call at any hour, day or night. Each agency in the EOC is provided with a small working space that consists of several telephones, a computer, access to TV monitors to monitor news coverage of the situation and a file draw to keep all important documents needed by the EPLO -- such as listings of available resources and personnel.

At the EOC, the EPLO – along with every other EPLO there – monitors the situation and provides assistance when needed.

Copyright 2007 Correctional Newsfront. Reprinted with permission.