Now you see them

By Deirdre Fedkenheuer

Reprinted with permission from the New Jersey Department of Corrections

The parking lot in a Mt. Laurel shopping center is strangely crowded, considering the time (about 5 a.m.) and the date (not the day after Thanksgiving). Coffee cups abound, as do vests, each displaying a law enforcement agency – New Jersey Department of Corrections, New Jersey State Police, FBI – and while the camaraderie is evident, so is the determination, as officers, all members of the New Jersey/ New York Regional Fugitive Task Force, huddle around Principal Investigator Ellis Allen and Senior Investigator Dan Klotz as they brief their comrades on the day’s quarry.

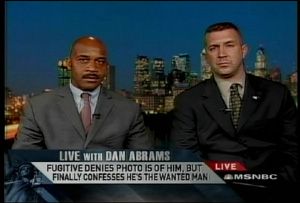

(NJDOC/MSNBC) Representing the New Jersey Department of Corrections Fugitive Unit during an interview on MSNBC are Ellis Allen (left) and Dan Klotz. |

Formed in 2002, the NJ/NY Regional Fugitive Task Force is an unprecedented law enforcement initiative that combines the resources, intelligence-gathering capabilities, investigative information and expertise of 50 law enforcement agencies and more than 150 federal, state, county and local law enforcement officers. Spearheaded by the U.S. Marshals Service, the Regional Fugitive Task Force represents the most ambitious cooperative law enforcement initiative ever undertaken in the State of New Jersey to target, identify and apprehend New Jersey’s “Most Wanted” fugitives.

In 2007 alone, the NJDOC Fugitive Unit made 85 apprehensions and countless others as members of the Regional Fugitive Task Force. Most absconders are out for just a few days, some for weeks, and still another very small segment is gone for decades. Most fugitives, when confronted, are peaceful.

“Their girlfriends or families talk to them on the phone and beg them to cooperate” says Allen. “They don’t want them to get hurt or to get charged with new offenses.”

But for the members of the Fugitive Unit, any apprehension can become dangerous in a second.

“You always have to keep in mind that they may be armed, they may be combative, they may have substance abuse issues,” Klotz points out. “These can combine to make a recipe for disaster.”

Klotz – described by co-workers as a bulldog – has been working on a so-called “cold case.” Inmate Maximo Jurado had absconded from the Marlboro Camp in 1979, and even though 28 years had passed, Jurado was never off the radar. He used fictitious names and Social Security numbers, and he moved around the country frequently, to include South Carolina, Pennsylvania and Connecticut throughout the years. However, Klotz was patient – and dogged. He developed information from contacts that Jurado, now 75, was living in Philadelphia.

“You look at their habits, you begin to see patterns in their life,” says Klotz, “and this guy is no exception.”

The briefing finished, the caravan moves into formation across the Ben Franklin Bridge and into Pennsylvania. Crown Victoria sedans, minivans and pickup trucks cross the Delaware River to meet up with officers from the Philadelphia Police Department.

Also in attendance this rainy morning is a reporter and photographer from the Associated Press and a public information officer from the NJDOC press office squeezed into the back seat of a minivan driven by Lt. Brian Slattery of the New Jersey State Police, with Ellis Allen riding shotgun.

Taking their assigned places down the street and around the corner from the suspect’s home, the waiting begins, as dawn reveals an urban landscape rife with broken crack vials, gang graffiti and empty beer bottles – from a fugitive’s point of view, a perfect place to “hide in plain sight.” A smattering of youngsters pick through the rubbish on their way to school, some showing mild interest in the “strange” cars parked on their street. But no children are seen leaving Jurado’s darkened home, and after a flurry of cell phone calls among team members, the decision is made to move on to another residence where the fugitive has been seen in recent days.

Despite the glamorous depictions in movies and television, “stakeouts” can be uncomfortable, monotonous and tiring, often punctuated with disappointment and false leads.

“There is going to be a certain amount of repetition in this job,” remarks Allen during the lull. “These guys (the fugitives) don’t understand we’re just going to keep coming after them. Doesn’t matter if they’re out for 10 minutes or 10 years, they owe the state their time, and everybody on this team is committed to keeping our streets safe.”

“Technology will only take you so far,” says Slattery. “Computers are very helpful, but you still have to pound the pavement and knock on a lot of doors.”

As morning slips into the afternoon, however, there is a sudden staccato of police radios and ringing cell phones, as the Philadelphia PD has spotted a car thought to belong to escapee Jurado parked several blocks away, in front of a female acquaintance’s apartment. “Wig wags” are activated, vests are adjusted and adrenaline is running high as members of the Fugitive Unit converge on the scene. Road closures, construction and a tractor trailer accident seemingly conspire to delay the team’s response. Klotz directs Investigator Robert Olmo and some of the vehicles to the street behind the girlfriend’s house to cover the back door, and desultory conversation among neighbors gives way to sharp knocking on the door and “Open up, Police!”

The young woman who answers the door is truly dazed as she looks at the officers and the camera that are parked on her stoop. She gestures for them to come inside and indicates that her boyfriend is up the stairs. Standing in his underwear, and bearing little resemblance to his mug shot of nearly 30 years ago, is Maximo Jurado.

At first, denial is the name of the game. Insisting his name is “Jose,” fugitive Jurado finally asks to see the photo the officers carry with them ¬– the photo that has been on the “escapee” page of the New Jersey Department of Corrections Web site these many years.

Investigator Jerome Scott has a comment for Jurado. “You’re going back to Jersey, OK?” he says. “You remember that photo? Remember that man, when he escaped from jail in 1979?”

Of course, the question begs to be asked: Why risk a life on the run, possible capture and longer prison sentence on a break out?

Says Klotz: “I asked him, ‘Why’d you leave? Why’d you escape?’ And he told me, ‘It was for a woman. She wouldn’t wait for me, so I had to go after her.’ I said, ‘Well, where is she now?’ He said, ‘She left me 20 years ago.’”

As Jurado is cuffed and led down the steps, Klotz remarks, “It took us a long time to get him but…" and Jurado finishes, “You got me.”

About the author

Deirdre Fedkenheuer is a public information officer with the State of New Jersey Department of Corrections.

Copyright 2008 NJDOC

Special thanks to Matt Schuman at the Office of Public Information, NJDOC

Has your agency implemeted a system that makes your job safer? Send us your story.