This article first appeared in Law Officer magazine

Subscribe

here.

In the June issue, the first installment of this series on investigating the crime of rape discussed legal definitions, the importance of care in handling the initial contact with a rape victim and the goals for searching the crime scene. I pointed out successful prosecution of the crime often hinges on associative evidence collaborating a rape occurred and linking a suspect to the scene and/or the victim. This second part focuses on the types of evidence investigators might collect and analyze at the crime scene and from the victim.

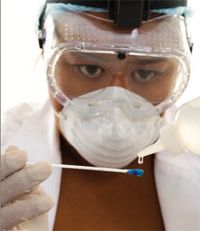

Evidence Identification & Collection

On-scene physical evidence is anything tangible that can establish a crime was committed or link the crime and the victim and/or the perpetrator and the victim. However, collection of physical evidence requires an investigator to first recognize such evidence. Further, the value of evidence is limited in court unless investigators take care to properly collect, preserve and analyze it.

Although many departments employ specialized personnel to process crime scenes, all police officers should possess a thorough knowledge of their crime laboratory’s forensic capabilities and understand the importance of securing and collecting evidence.

While there is no substitute for training and experience, the collection and preservation of crime-scene evidence is not just the purview of evidence technicians and detectives. Except in very complex cases, the average police officer is capable of reconstructing the scene of the crime and conducting a systematic search for evidence.

As I explained in my previous column, in a rape there are two crime scenes: the location where the rape took place and the rape victim’s physical person, including the clothing worn by the victim and the perpetrator.

Studies indicate up to 80 percent of rapes occur indoors, and the majority of cases involve some type of relationship between the victim and perpetrator. Unless it’s a stranger-to-stranger rape case, the perpetrator often claims intercourse was consensual, and without any associative evidence to the contrary, the victim’s word is pitted against the perpetrator’s claims. So, investigators should photograph and videotape any sign of a struggle at the scene, such as broken furniture or other objects and items in disarray. Further evidence of a struggle includes injury to the victim; these photographs are normally taken at the hospital.

Preserve the bedding, or any other object on which the rape took place, and send it to the crime lab for analysis. The contact between the victim and the perpetrator may have resulted in the transfer of physical evidence in the form of semen, blood, hairs, skin fibers or other trace evidence, which will prove vital in identifying the assailant and/or prosecuting the case.

Properly collect all such evidence, including the clothing and undergarments worn by the victim. Evidence technicians use oblique and ultraviolet light to help spot hair and fibers, and blue light to assist in detecting semen.

One discrepancy between books on forensic science and real-life investigations is the suggestion the victim should be asked to disrobe over a clean cloth or bed sheet so any fibers or loose pubic hairs from the perpetrator can be properly collected. In an ideal world, this would be the perfect way to collect this type of evidence.

However, only in the mind of the scientist or academician do rapes occur in a sterile environment conducive to this type of evidence collection. Although most rapes do occur inside, the crime scene may be the stairway of large apartment building, the bathroom of a bar or nightclub, the inside of a vehicle or some other location not conducive to this type of evidence gathering.

Whether the victim is suffering from shock, lying in a fetal ball or is otherwise injured from her attacker, our first responsibility is to provide the victim with medical attention at a hospital. Even if the victim were able to disrobe at the scene, this must be conducted by a female police officer. Since female officers make up only about 12 percent of police forces nationally, a female officer may not be readily available to provide this type of evidence collection.

In the majority of cases, a search of the victim’s clothing for crime evidence is done at the hospital. This is often a better setting in which to ask the victim to disrobe, take photographs of any injuries to her body and place each article of clothing in a separate container for later lab analysis. The chain of custody of evidence is vital, so a police officer must accompany the victim to the hospital, meaning an officer must ride in the ambulance with the victim.

The Medical Examination

Even if your department employs personnel who specialize in investigating rape crimes, not all hospitals are equal when it comes to conducting the necessary type of medical examination. Hospitals in large cities often staff medical personnel with specialized training in the physical examinations required, as well as rape counselors who can provide psychological services for the victim. Smaller communities may have only one hospital, which may not be able to provide that level of service.

Big city or small town, the fact remains doctors are not usually in the business of evidence collection. Although rape victim collection kits are standard issue at almost every medical facility, this does not mean medical practitioners will collect evidence properly. Those in charge of the department’s investigative function must take responsibility for ensuring the proper liaison exists between the department and the community’s hospital(s). This means meeting with doctors and staff, and explaining the nuances of the necessity for evidence and the information it can provide (see “The Medical Examination: Collection of Physical Evidence”). Ahospital staff meeting is an opportune time for police and medical professionals to discuss not only how they will work together to handle rape cases, but also how they will preserve the chain of custody of evidence.

The associative evidence collected during the medical examination proves most useful in cases where the victim does not know the perpetrator. However, even if investigators know the victim’s assailant and make an arrest shortly after the crime based on probable cause, it’s still critical all evidence protocols described in this article be followed. Arrest only requires probable cause. Conviction in court requires a much higher standard: proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Experienced investigators know the variables under which an arrest is initially made can change for various reasons: the evidence does not support the initial claims of the victim or witnesses, people change their versions of what they initially say occurred, the perpetrator claims sex was consensual and so on. Our system of justice relies heavily on tangible evidence, because emotion or perception does not affect it and logical conclusions can be drawn from the science supporting what the evidence represents.

As I stated earlier, investigators must photograph any physical injury to the victim, such as bruises and bleeding. Biological evidence, such as semen, may indicate sexual intercourse did take place, but that does not establish a prima facie case of rape. Injury to the victim is corroborative evidence of violence and is especially useful in cases where the suspect claims consensual sex.

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA)

The discovery of DNA has revolutionized criminal investigation. An individual’s identity can be obtained from sweat, skin, blood, tissue, hair, semen, mucus, saliva and almost any biological sample. The evidence collected at the crime scene and during the medical examination of the victim is crucial to obtaining DNA evidence that may identify the perpetrator. If there is a suspect in the case, there are several ways to obtain a DNA sample, including voluntarily, surreptitiously and under court order as a result of a search warrant. I prefer obtaining a search warrant, because even a signed authorization from the suspect proving “knowing and intelligent consent” or a “legal” search through a person’s trash for a discarded napkin containing saliva is fraught with legal challenges.

Voluntary Submission

People can’t be forced to provide a DNA sample. Investigators must obtain a signed and witnessed authorization form from the suspect. The form contains language similar to the Miranda rights waiver, and includes consent to an oral swab and/or a blood sample for the purposes of DNA testing. Instructing a suspect to swab his inside cheek is a simple procedure any police officer can conduct.

Surreptitious Obtainment

Because DNA can be obtained from biological material, anything containing saliva, mucus, skin, etc. may be used to obtain an individual’s DNA typing. The key is the suspect must have discarded an item, such as a cigarette butt, in a public place to which the police have legal access. A soda can, food or napkins may contain skin cells or saliva from inside the suspect’s mouth, which could result in a DNA typing, linking the suspect to the rape.

Search Warrant

Because search warrants must specifically declare the evidence sought, investigators must list any objects or samples from which a DNA analysis can be obtained. This might include the suspect’s clothing and anything that might contain blood or semen stains. Clothing worn by the suspect must be legally obtained. If the suspect is under arrest, investigators could theoretically seize the clothing without a warrant. However, as I mentioned earlier, a search and seizure warrant is the preferred method of obtaining DNA evidence because the likelihood of such evidence being admitted in court is substantially greater than when the suspect voluntarily submits evidence or when it’s obtained in a surreptitious manner or as part of a search incidental to arrest.

The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS)

In cases where the rapist is not known to the victim, investigators can submit DNA typing of biological material recovered from the crime scene to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s database of DNA profiles from convicted offenders, unsolved crime scenes and missing persons. All states mandate the collection of DNA samples of convicted rapists, a tool that allows crime laboratories to electronically compare DNA profiles from those developed in the investigation to a national database. This is yet another example of how science and technology are merging to dramatically change criminal investigation from an art into a science.

The next installment of this rape investigation series will bring together the concepts from the first two articles by discussing the investigation of the hypothetical case of Marie Delaney, a bank vice president who was raped and left for dead in a parking garage while returning to her car.

|

The Medical Examination: Collection of Physical Evidence

|