Sponsored by Smiths Detection

By Philip J. Swift for Corrections1 BrandFocus

The primary goal of any contraband interdiction program is the accurate and rapid detection of contraband concealed on or about a person or package. The most effective way to interdict contraband is to focus on individuals who move in and out of secure areas or otherwise have direct contact with inmates.

Often the most significant mass movement of people in and out of the secure areas of a facility occurs during visiting hours. Visits are extremely important to inmates because they offer a break in the routine and allow inmates to have face-to-face interactions with their loved ones or with service providers such as lawyers, chaplains, drug rehab counselors, etc. Due to this fact, inmates and their families take full advantage of visiting hours, guaranteeing a large amount of movement facility-wide.

Whether conducting personal or professional visits, corrections officers are required to move visitors in and out of the visiting area in an organized and timely manner, stop intentional or accidental contraband introduction and maintain the safety of the visitors, inmates and staff. While carrying out these tasks, every corrections officer knows that a failure in these duties could result in the introduction of dangerous contraband, disruptive inmate behaviors, complaints and allegations of constitutional abuses related to restricted visiting.

CATCHING CONTRABAND IS AN ONGOING CHALLENGE

While tasked with carrying out personal visits and, at other times, official visits, I can tell you that the repetition and monotony of the job became bothersome for both the visitor and me. Further, when crunched for time, it was easy to take shortcuts in the screening process or to “stop seeing” what was being displayed on the X-ray machine because it looked almost the same as the last 100 times you looked at it – not to mention the looks and comments that were hurled my way by visitors because I took the time to look twice at an image or, God forbid, I backed the belt up on the X-ray machine or rescanned an object.

Everyone involved in the corrections field understands that fatigue, stress and multitasking reduces our ability to concentrate and complete tasks efficiently and effectively, but how much do these issues impact corrections officers’ ability to recognize contraband items?

I have investigated and charged enough people for introducing contraband to jail after it has already made it through the screening process to know that we are not as effective as we could be at recognizing contraband early enough to stop its introduction to a secure area.

MAINTAINING FOCUS IS CRITICAL

If we know that we are relatively bad at a particular task or at least less efficient than the task requires – in this case, 100% accuracy with a track record of being less than 5% successful – the question becomes what we can do to fix it? Generally, the barriers to an effective screening process include but are not limited to hardware and software costs, staffing costs, training costs and longer screening times.

The weakest link in the chain in most screening processes is the ability of the operator to recognize contraband. The quickest way to reduce human error is automation, which has been proved repeatedly on assembly lines worldwide. For automation to be practical, it must be cost-effective, increase accuracy and create a positive flow. When positive flow is achieved, the majority of people can move through the screening area with little or no delay, while only those carrying suspected contraband items are flagged for closer scrutiny.

For example, facial recognition and license plate readers have created a positive flow screening process by automatically determining if a person is wanted prior to an officer taking action. At the same time, the vast majority of the public is unaware of the screening process and goes about their day unimpeded.

SEE MORE WITH SOFTWARE FROM SMITHS DETECTION

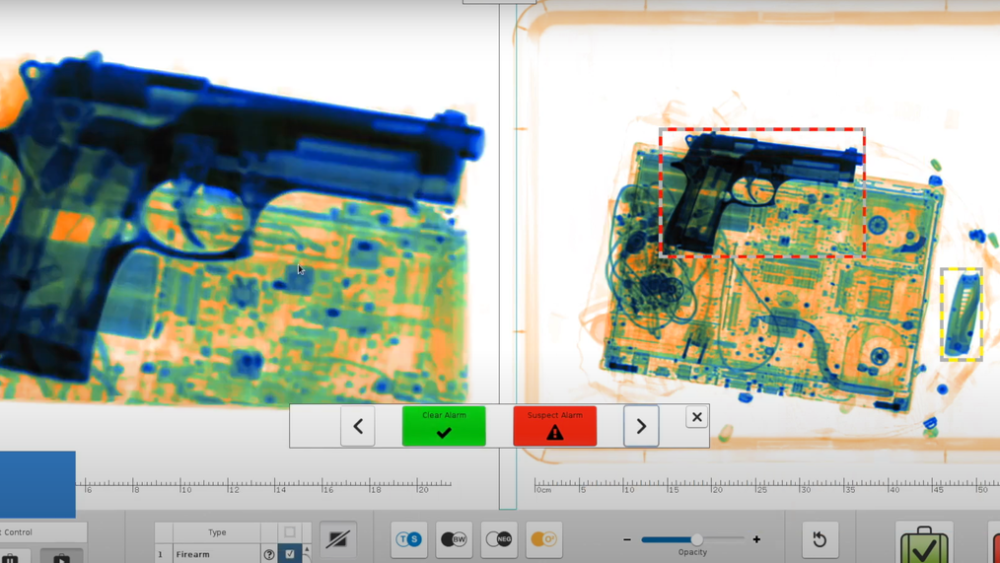

To improve and automate the screening process, Smiths Detection has designed object recognition software called iCMORE that works in conjunction with their existing X-ray equipment. The software uses advanced algorithms to reduce the burden on operators – as well as potential errors – by automating the detection process for suspicious items. iCMORE automatically identifies:

- Guns.

- Gun parts.

- Ammunition.

- Knives (minimum blade length of 6 centimeters, overall length of 15 cm).

- Lithium batteries.

- Flammable liquids and solids.

- Liquefied or compressed gases.

- Cash ($100 bills in single bundles).

- Other dangerous items.

This automatic recognition improves accuracy by reducing human error caused by fatigue and repetition. (It reduces the risk of eyestrain to COs as well.) Automatic object recognition also improves positive flow during the screening process because operators don’t need to stop the conveyor belt for closer inspection of a suspicious item.

Adding iCMORE software to your screening process can also reduce the liability associated with the use and abuse of contraband by inmates by reducing the number of unintentional or intentional introduction cases. Implementation of iCMORE requires little or no additional training and is available in conjunction with various Smiths Detection X-ray screening equipment.

Visit Smiths Detection for more information on iCMORE.

Read Next: Shut the back door on contraband and contaminated food

About the author

Philip J. Swift is currently serving as a city marshal in the DFW area of Texas and has been a law enforcement officer since 1998. He holds a Ph.D. in forensic psychology, and his areas of research include behavioral learning theory, cognitive schemes, group psychology and historical trauma theory. He has several published works and regularly speaks locally and nationally regarding his research and expertise in law enforcement and criminal culture.