Ed’s Note: In most jurisdictions, mail can be read by officers, with the exception of legal correspondence between the inmate and his attorney. We should take the time to perform this mundane task, as we never know what we will find. In today’s C1 Exclusive, Barry Evert tells you what red flags to look for on outgoing mail. Red flags on mail correspondence.

By Daniel Borunda and Erica Molina Johnson

El Paso Times

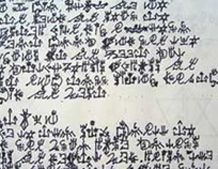

EL PASO — Multi-layered and often confusing codes allegedly used by Barrio Azteca gang leaders in prison to communicate with gang members in the streets form a cornerstone of one of the largest gangland trials in El Paso currently under way in U.S. District Court.

Prosecutors allege in a federal Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization, or RICO, case that members of the gang conspired to raise money for capos, or leaders, in prison by extorting street-level drug dealers in El Paso with “quotas” on drug sales.

“They all have to be kept in codes. So officers, the law, the man, won’t be able to figure out what you are saying,” testified Johnny “Conejo” Michelletti, a former soldier in the Barrio Azteca turned government witness.

Testimony by former Aztecas and investigators shined a light into a complex communication system in which suspected capos in maximum-security prisons were allegedly able to issue orders on the street through the gang’s paramilitary hierarchy.

The trial for six accused gang leaders, members and an associate continues Monday before U.S. District Judge David Briones.

Code words used in letters and conversations were in English, Spanish, Spanglish and even Nahuatl, the Aztec language, all in an attempt to throw off “G.I.s” or gang investigators.

Former Azteca sergeant Gerardo Hernandez testified the organization trained members to read and write in gang slang.

“I was taught that,” Hernandez said. He said the gang called the instruction of the coded language “escuela,” Spanish for school.

Hernandez said that letters or wilas are passed along by inmates and occasionally by corrections officers while he was incarcerated in a facility in Otero County.

“Almost every day we would get letters from the whole (prison) system,” Hernandez said.

To the untrained, the messages could be a nonsensical collection of words.

FBI Special Agent Samantha Mikeska, who led the Barrio Azteca investigation, testified that over several years she has kept a list of coded words and their meanings to better understand the gang’s language.

“It would be difficult to know the meaning of a letter without a code sheet,” she said.

Her glossary has continued to grow throughout the trial, which has lasted more than two weeks.

In code, Aztecas were identified by variations of their nickname, the street they lived on, prison identification number or occupation, witnesses testified.

For example, suspected gang capo Carlos Perea, nicknamed “Shotgun,” was also allegedly identified as escopeta (shotgun), 12-gauge and doce, Spanish for 12, witnesses testified.

Various words stood for numbers. For example, one sentence used the words asesino (assassin), cuaderno (notebook) and nariz (nose), which meant $1,400, Andres Sanchez, an El Paso police gang investigator, testified. Translated -- asesino refers to ace meaning one, cuaderno similar to quad meaning four and nariz for nada or zero. Also, bufalo, as in a buffalo nickel, means five.

Vivek Grover, lawyer for suspected capo Manuel Cardoza, argued that just because a letter may be in code or was requesting money be placed in a prison account does not make it illegal.

“There is nothing to indicate where the source of that money will be,” Grover said in court.

Prosecutors allege the source of the money was quotas, also known as taxes and rentas, extorted from “tiendas,” slang for drug dealers.

With coded messages, prosecutors also claim that slayings could be ordered from prison cells hundreds of miles away.

Sanchez, the gang investigator, and Perea’s lawyer Gary Weiser debated in court the meaning of “Tony Lama.”

Weiser said Tony Lama referred to someone getting the boot or kicked out of the gang. Sanchez said it means murder. The debate was related to a letter that supposedly threatened the life of reputed capo David “Chicho” Meraz, who was slain last March in Juárez.

Meraz, who had apparently fled across the border, was allegedly involved in a power struggle years ago with Miguel Angel “Angelillo” Esqueda over who would run Barrio Azteca’s operations in El Paso, according to testimony.

“Attempts were made to warn David Meraz,” Sanchez said. "... We could not locate him.”

Copyright 2008 El Paso Times, a MediaNews Group Newspaper

Prison gangs in the news:

Probers say street gangs more active in NJ prisons

Investigation: Bloods exploiting NJ jails

Agencies join forces to tackle violent gangs

An inside fight against gangs in N.J. jail

C1 Related

Compromising the integrity of staff in prison, Part 1 — Are you at risk?

Survival of the fittest: Staying ahead of prison gangs