Part 3 of 4

Read full series

People respect and fear electricity. Who has not received a small jolt on a dry day from a door knob or even from the touch of a loved one? This passing familiarity with electricity has bred contempt. While it is true that groups like Amnesty International and the ACLU are taking a run at all less lethal weapons, the one that is most often in their crosshairs are Electronic Control Devices (ECDs).

For that reason we must have a thorough understanding of what these devices do, what they don’t do, and when it is best to use them.

There are several different types of electronic control devices. Most of them are better suited for a correctional environment or courts than they are for patrol. The use of ECDs in patrol is almost exclusively about apprehension, but many ECDs serve other functions. Currently, ECDs can be broken down into the following categories: cuffs and belts, shields and hand-held devices.

All ECDs generate between 40,000 to 80,000 volts, though this much voltage does not enter the body. To the electronically illiterate brought up on misleading warning signs that read, “Danger! High Voltage,” this seems like a high number. But high voltage does not kill. High amperage kills. All these devices generate a negligible amount of amperage. In that regard they are similar, but the technology in TASER International’s devices is significantly different from that in all other ECDs.

All less lethal weapons use pain compliance in an effort to modify behavior. The biggest advantage to any ECD is that its effects end almost immediately after the weapon is deactivated. Impact munitions can cause significant injuries. Chemical agents are the gift that keeps on giving. It is rare when exposure to an ECD results in more serious injury than minor skin irritation. And, despite claims to the contrary, they have not been shown in research or field applications to cause death.

So which ECD should you use? And when should you use it?

Cuffs and belts

These tools are primarily used for prisoner escort and transportation. They are remotely operated and thus provide the advantage of standoff distance between the inmate and the deputy or officer manning the controls.

These devices deliver pain to sensory nerves. In that regard they are effective. The question is when should you use them? Every agency sets its own standards for the use of force. Still, when a suspect is already in handcuffs or other restraints the perception is that he is under control. All of us on this side of the badge know that a person in handcuffs still poses a potential threat.

Some inmates are so violent they are always transported in manacles, ride in a safety chair and wear a spit mask. Would you ever apply a jolt from a shock belt or cuff to a man so secured? Unless he is breaking out of those restraints, I hope your answer is no. Common sense dictates that an inmate in restraints needs to act out in a manner far more significantly than a non-secured inmate prior to the application of force.

Unfortunately, common sense is not always common. In July 1998 an inmate facing trial for his third strike was seated in a Southern California courtroom wearing a shock belt. The suspect was speaking out of turn and angering the judge. He refused to be quiet when ordered to do so. Frustrated with this behavior, the judge ordered her bailiff to activate the shock belt. The sheriff’s deputy followed the order of his judge and the suspect received an eight second jolt that stopped his disrespectful behavior. It also effectively ended the shock belt as a tool for my department.

Be careful when and how you use these devices. Also, be mindful that though delivering pain to sensory nerves is almost always effective against law enforcement personnel in training demonstrations, focused aggressors can fight through pain. Be prepared to

|  |

follow up your use of these devices with control techniques or other tools.

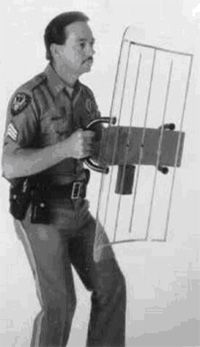

Shields

The electronic shield comes in one of two types: convex for riots and concave for capture. In other words, concave electronic shields are for pushing and convex shields are for pinning. Shields are typically seen as defensive. Having an electronic component to a shield gives it an offensive bite. However, the use of any shields, whether equipped with an electronic capability or not, is limited.

The Nova Electronic shield produces 75,000 volts at 17 to 22 pulses per second. Throttling the shield produces a crackling, popping and arcing that has a wonderful intimidating factor. This may be the tools strength against less than committed inmates. You throttle this a time or two with a fully suited up extraction team nearby and you may not need to do the extraction. The problem comes when you actually enter the cell.

If an inmate is so focused that they do not care what less lethal tool you employ, then one shield is a lot like any other. And in a cell extraction the role of the shield is primarily to drive an inmate against a wall and then pin him while the takedown team moves in. Once the inmate is on the ground the shield is removed. There is no other way to secure the inmate.

The dynamics of a riot or disturbance in corrections is different than one on the street. Inmates are always confined, whether it is by a dorm, dayroom, yard or other area. In most jail riots the majority of inmates do not want to be there and are waiting for the intervention of staff to give up.

If multiple inmates are still acting out when staff appear, you are going to employ less lethal tools that give you the greatest standoff distance and flexibility. Shields do not give you that. If you use them at all, you are again going to want to use the convex capture shields so you can both deflect thrown objects and then pin inmates when the tables turn. Due to the inherently defensive nature of shields the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department almost never uses them during jail disturbances. I would be interested to hear what success any of you have had with ECD shields in inmate disturbances.

Hand-held devices

|  |

There are a few competing hand-held ECDs on the market today, but only TASER International’s M26 and X26 do more than attempt to modify an inmate’s behavior with pain. Pain is a great motivator. But chemicals, alcohol and adrenalin can reduce pain’s motivating qualities. There is also a small portion of very scary humans out there who are almost impervious to pain. The M26 and X26 impact both the sensory and motor nerves. They cause the muscles between the area impacted by the darts to lockup. Probe to skin contact is not even required for this to occur.

Hand-held TASERs can be used in numerous situations within jails and prisons, but in order for them to be most effective they must be routinely deployed. Do not lock them away in an armory and only break them out in emergencies. Some times just removing a TASER from its holster, taking off the cartridge and pulling the trigger in a spark demonstration is enough to modify an inmate’s behavior and gain compliance before a situation gets out of hand. But this can’t happen if they are kept in an armory.

Inmate fights and aggression against staff

This one is a no-brainer, but there are a few things to consider. Back and leg shots are best because they involve larger muscle groups. Also, try to achieve a probe spread of at least four inches to ensure a sufficient lockup of the muscles to cause incapacitation. If the dynamics of the situation dictate a close probe shot the probe separation may not be wide enough to cause incapacitation.

If the inmate is not incapacitated and is still a threat, you can apply a drive stun with the cartridge still attached to increase the effectiveness. This is called a close probe spread with a drive stun follow up because you have two darts in the inmate and the two contacts on the TASER Cartridge affecting another part of the body. This should increase the effectiveness and may cause incapacitation.

The further apart the probes strike the inmate the more effective they will be. If you miss with one of the probes, you can apply a drive stun leaving the TASER Cartridge attached. The attached TASER Cartridge will act like the second probe completing the circuit and should cause incapacitation. This is called a one probe hit with a drive stun follow up. In this case push the inmate away from you, reload a second cartridge and fire again.

If two inmates are fighting and are in contact with each other, it is possible to affect both inmates with one TASER Cartridge. You may need to turn the TASER slightly to ensure that the top dart contacts one inmate and the lower dart the other. Since they are touching each other the circuit will be completed between them. This is very effective and I have seen it work on multiple occasions.

Cell extractions

During cell extractions inmates usually don their own makeshift protective gear or cover up with a mattress. This makes firing the darts problematic. You may need to employ other less lethal tools such as distraction devices to create an opening to fire the TASER. If this fails, using the TASER with the cartridge removed may be an option.

There are two schools of thought on drive stuns in cell extractions. One employs the cartridge and darts. The other does not. If you use the TASER without employing the cartridge, you will not be locking up the muscles of the inmate. Unless you are lucky enough to find a pressure point (not an easy thing to do in a confined space with numerous staff members and a twisting fighting suspect) all you are doing is applying pain and inflicting a visible injury or injuries to the inmate’s skin as you wrestle him into submission.

Attempt a close probe shot with a drive stun follow up leaving the cartridge attached.

In this case fire the darts into one of the inmate’s upper legs or thighs, then drive stun the lower portion of the opposite leg. This should lock up his entire lower body. I prefer this method, but in a recent incident at my jail where numerous inmates in one man cells were extracted the supervisors on the scene felt the space was too confined and the wires would come in contact with the extracting deputies. So they opted for drive stuns without the cartridges.

It worked for them and the inmates I spoke to afterward told me that it was very effective. If the situation presents itself, try both methods and see what works best for you.

Prisoner escorts and transportation

Again, before attaching any ECD to an inmate we are assuming that he is high risk and or extremely recalcitrant and is handcuffed whenever he is escorted. There are advantages and disadvantages to using the TASER in prisoner escorts and transportation. The disadvantages are you must be in close proximity to the inmate and there will be trailing wires attached to him so the fact that he is hooked up to the TASER cannot be concealed. The advantage to using the TASER is that unlike with other ECDs activating the TASER can cause incapacitation in addition to causing pain.

To use the M26 or X26 as an escort tool you must use the special training cartridge pictured above. This cartridge is equipped with thick insulated wires with alligator clips at the end. Affix the alligator clips to the inmate and tape them down to ensure the inmate does not shake them loose. If the inmate begins to resist or attempts to break free, the TASER can be activated to help achieve control. Hopefully, this activation alone will modify the inmate’s behavior enough for you to gain control, but again be prepared to go to hands on and the application of some other form of restraint.

Inmate countermeasures

Inmates who have experience with the TASER may attempt to defeat it in a number of ways. Covering up works in cell extractions, but is less effective when they are out in the open. Another technique they have tried is whirling towels or clothing in front of them like a propeller in an effort to deflect the darts and wires. Attempt to flank the inmate with a second TASER in this situation. But even if one is not immediately available, while an inmate is spinning his makeshift propeller he is not aggressing you and other staff can respond to your aid.

After a good dart hit is made every effort should be made to end an inmate’s aggressive behavior while the TASER is still activated. This is referred to as handcuffing under power. When the trigger on an M26 or X26 is pulled the weapon launches the darts and the device is activated for a five second cycle.

Bad guys have learned this, too. Many have learned to tough out those five seconds and then attempt to defeat the device by breaking the wires either by rolling or grabbing them before the TASER can be reactivated. The best way to prevent this is to control/cuff the inmate during the 5 -second cycle, if possible.

Unless you and your partners are calf roping champions this is highly unlikely, however. Keeping the trigger depressed past the 5 - second cycle extends the cycle until the trigger is released. This should thwart the inmate’s efforts to attempt this countermeasure, be prepared to justify this non-standard longer cycle in your force documentation.

Guarding against abuse

Some jails and prisons have stopped using ECDs because of allegations of abuses and misuses of them in the past. These abuses predated the M26 and X26. Both of these devices record their firing data. In the case of the X26, the date, time and duration of activation is logged.

This data is encrypted and cannot be manipulated. Also, in 2006 TASER came out with the TASER CAM. This infrared camera is mounted to the base of an X26, can work in zero light, if necessary, and begins recording as soon as the weapon is taken off safe. These features both guard against claims of abuse and in the case of the TASER CAM can document an inmate’s behavior prior to the activation of the TASER. I have used the TASER CAM many times without ever firing the TASER to document an inmate’s actions. All the black and white photos in this article with XCE000139 in the bottom left hand corner are from my TASER CAM.

Conclusion

ECDs are an effective tool for use in corrections, but even the M26 and X26 are still transitioning tools, not finishing techniques. Do not expect the application of an ECD to end your problem. You still need to be ready to move in and secure the inmate to end the behavior that caused you to employ the ECD in the first place. Still, the M26 and X26 are as close to phasers on stun as we are likely to get in law enforcement. Make sure you employ all ECDs wisely.

About the author

John J. Stanley, M.A., is a twenty-one year veteran of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. He has worked a variety of assignments including, custody, patrol, training and administrative support. He is also a published historian and has written extensively on the history of law enforcement and corrections. He is considered an expert in less lethal weapons and tactics and is currently a member of the TASER International’s Corrections Board. He provided corrections scenarios for the Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies Applied Research Laboratory at Penn State University and contributed to its on-line Less Lethal Weapons class. John spent over a decade at LASD’s Custody Training Unit teaching classes such as Tactical Communications, Jail Intelligence Gathering, Tactical Weapons, Squad Tactics and Cell Extractions. John also was the lead instructor for LASD’s Custody Incident Command School (CICS) a class designed for sergeants and lieutenants and the Executive Incident Command School (EICS) for captains and above. He is also a member of the teaching cadre for LASD’s Tactical Science class offered to police personnel from all over the United States. John is currently a sergeant assigned to the Men’s Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles. He is also a squad leader and trainer on LASD’s newly formed Sheriff’s Response Team (SRT), a unit created to handle crowd control, jail and civil disturbances, and respond to natural disasters and terrorist attacks.